Oakland 4th-grader performs ancient art

By TERENCE CHEAAssociated Press

Writer

OAKLAND, Calif. (AP) — Tyler Thompson isn’t much different from other fourth-graders in his Oakland neighborhood. He likes basketball and pro wrestling, cartoons and comic books.

But Tyler has a talent that sets him apart from his peers: He performs Chinese opera.

The 9-year-old, growing up in a city more notable for its tough streets than its touches of culture, is bringing crowds to their feet around the San Francisco Bay Area with his uncanny ability to sing in Mandarin Chinese. It’s a language he doesn’t speak but sings like a native.

“It’s shocking for the Chinese. Here’s an African-American kid learning an art form that even the Chinese for the most part rejected or misunderstood,” said David Lei, chairman of San Francisco’s Chinese Performing Arts Foundation.

He first saw Tyler perform last year at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum.

“He had a good voice and was very accurate in his singing,” Lei said. “It wasn’t chop suey. It was the real thing.” Tyler quickly became one of Northern California’s most popular Chinese music performers, wowing audiences at Oakland City Hall, the Herbst Theater in San Francisco and HP Pavilion in San Jose.

The San Jose event was filmed by China Central Television, which will broadcast his performance during its annual Lunar New Year extravaganza, a program seen by hundreds of millions in China and elsewhere around the world.

On Saturday, Tyler will be a featured performer at the San Francisco Symphony’s annual Chinese New Year concert, just four days before the Year of the Rooster begins on Wednesday. He will sing a Chinese folk song accompanied by a Chinese instrument ensemble.

“Chinese singing has gotten me this far, so I’m going to stick with it,” Tyler said.

Tyler learned how to sing Chinese songs as a student at Lincoln Elementary, a public school in Oakland’s Chinatown where 90 percent of students are Asian, mostly children of working-class Chinese immigrants.

It’s one of the nation’s few public schools with a Chinese music program, started 10 years ago by teacher Sherlyn Chew, who was born in Oakland and attended Lincoln as a child.

She teaches students of all backgrounds to sing Chinese songs and play traditional Chinese instruments.

Tyler’s mother, Vanessa Ladson, said she chose Lincoln because of its high academic standards, as well as its proximity to her job at a utility company.

Tyler has always loved music, Ladson said. Not long after he learned to speak, he’d sing with his father when they drove together in his truck. He grew up singing whatever music his mom played at home, from gospel to jazz and R&B.

“Tyler lives to sing, period,” Ladson said.

Chew said she first recognized Tyler’s talent and his “angelic” voice when he was a spunky kindergartner.

“He had a very nice voice, he could sing in tune, his timing was good, and he picked up songs very quickly,” Chew said. “When I asked who would like to sing by themselves, he would be the first to raise his hand.”

Ladson was driving Tyler home from school one day when she first heard him sing in a different language. She couldn’t believe it, and asked him to sing the song three times.

“I went home and said to his father, `Do you know Tyler is singing in Chinese?'” Ladson said.

A few years ago, Tyler asked his mother if he could join a weekend music program Chew had started at Oakland’s Laney College. Its goal was to teach students who wanted to pursue their interest in playing Chinese instruments or singing Chinese songs.

Tyler doesn’t speak Mandarin, a tonal language in which the same word spoken with a different tone has a different meaning. But Chew taught him and other students who didn’t speak Chinese by spelling out the words and teaching them how to sing with the correct pronunciation and intonation.

“Each syllable is clear. His tones are very good,” Chew said.

“He doesn’t speak the language, but he knows the meaning of the song. He knows what he’s trying to convey to the audience.”

At Tyler’s first performance, during Lincoln’s annual spring concert, he sang a Mongolian folk song about a young man who misses his friend in winter.

“When the spring comes and the snow melts, I wonder if she will remember me?” Tyler sang in Chinese.

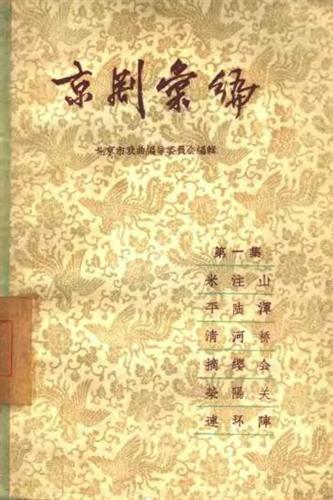

“He sang so well that people were moved to tears. Then I said I’m going to teach him Beijing opera,” Chew said. “It’s a lot more complicated, but I thought he was ready.”

Beijing opera, one of many forms of Chinese opera, is a centuries-old art form that blends highly stylized dancing, acting, acrobatics and pitched singing that Westerners might find jarring. Once a dominant form of art and entertainment in China, Chinese opera’s popularity has steadily declined.

“It’s dying because it takes so much effort to learn,” Lei said.

“This art form must grow on you. It’s an acquired taste. But once you acquire it, you really love it.”

Tyler said learning to sing in Chinese has helped him solve one of life’s biggest questions.

“Before, I never knew what I was going to be when I grew up,” he said. “But now I know what I’m going to be … a Chinese music singer.”

新华社的稿子中,将其中介绍京剧的部分省略掉了,大约是因为那部分是给不懂京剧的洋人看的,而如果读者是国人自然不需要了。但,那一部分恰恰是最需要引起国人关注的:“京剧,曾经一度是在中国占主导地位的艺术及娱乐形式,其流行度持续下滑。雷说,京剧之所以在灭亡是因为需要花很大功夫去学它。这种艺术形式一旦吸引了你,你将会非常喜爱它。”